In reflecting upon and writing about this annotation flash mob, I recognize how this pedagogical experiment was only possible because of many generous individuals who write, share, and – to put it simply – work just so dang hard to ensure that the technical, the social, and the playful all come together. Thank you Sean Michael Morris, Jesse Stommel, Hybrid Pedagogy, and the Digital Pedagogy Lab. And thank you Dan Whaley, Jon Udell, Jeremy Dean, Nick Stenning, and others at Hypothesis. I am grateful for your support and inspired by your work. – Remi

On less than 24 hours notice, toward the semester’s end, and coinciding with the due date of INTE 5320 Games and Learning’s affinity spaces project, my graduate learners and I organized an annotation flash mob. Yes, I did write up a flash mob invitation, two #ILT5320 learners graciously volunteered to help facilitate (thanks Tedy and Nik!), and various tweeps helped to spread the word far and wide, though apparently there really wasn’t a plan:

@remiholden Do we have a plan for this? flash mobs usually have some kind of choreography 🙂 #ilt5320

— Lisa (Butler) Dise (@Peachey_Pie) April 25, 2016

Despite circumstances that were less than ideal, ambiguous direction, and expectations that were very likely unrealistic and unrealizable, about 20 people came together and utilized Hypothesis to flash mob annotate Sean Michael Morris’ recent #digped article “Teaching in our Right Minds: Critical Digital Pedagogy and the Response to the New.”

Seven of INTE 5320’s 11 graduate learners participated. A who’s who of open pedagogy scholars and web annotation advocates joined, too, including Maha Bali, Robin DeRosa, Jamila Siddiqui, Joe Dillon, Jeremy Dean, Alexandre Enkerli, and Roy Kamada. And individuals I’ve never met before – like Britni Brown O’Donnell – and those whom I may never know (or whose Hypothesis handles I don’t recognize) also participated – thanks for your contributions Gandalf511 and mcjsa! We also received simultaneous engagement via Twitter, specifically from Sean Michael Morris, Jesse Stommel, and VTE (Vitrine technologie-éducation) Live, and subsequently many inquiries and likes – so yes, we’ll make plans for another bit of playful learning Christopher Haynes.

As of this writing, there are 85 annotations with many, many replies. There are embedded images, GIFs, and videos. And conversations about posthumanist literature, the affordances and nerd-love associated with “labs,” respect and empathy needed when designing and learning with educators, and the provenance of the Apatosaurus. And perhaps these varied – and very meaningful – conversations are just getting started:

Most flashmobs are shortlived. Sounds like the #ILT5320 is only getting started. May morph into asynchronous tates. https://t.co/xygOYCmczT

— VTE Live (@vtelive) April 26, 2016

I’ve written previously about how open web annotation appropriates (con)texts. In the case of this flash mob, the individuals who became an ad hoc collective appropriated: a) Sean’s text as the theatre within which we played; b) the multiple contexts of established social routines, from open web annotation as social reading, to the impromptu activities of a flash mob, to a broader frame of online and digital teaching and learning; and c) a hybrid (con)text mashing up formal with informal learning, participants in a university graduate course with a distributed network of learners, and academic with social expression. The hybrid nature of participation in – and across – time was also apparent; the flurry of synchronous activity bounded by about an hour of intense flash mobbing has been complemented by subsequent (and ongoing, and open-ended) asynchronous contributions. And, as will be noted momentarily, acts of reading and writing emerged from the margins and spanned other platforms and media.

If you haven’t done so already, go read our annotations – they’re wild.

And since this flash mob concluded I’ve been begun to consider this question: What might it mean to read and write an annotation flash mob? The remainder of this post shares my thoughts associated with this question – thoughts that are provisional, at times conflicting, and quite exploratory.

During the flash mob my social reading – and ongoing activity as a writer – was not confined to a single online platform or setting. That is, I was not only reading and then writing in the margins of Sean’s Hybrid Pedagogy article. Participants may agree that Roy’s comment accurately captured their stance in the moments before the flash mob.

Hovering over @slamteacher’s article, waiting for annotation flash mob with @remiholden #digped https://t.co/vqedUUGUZO

— Roy Kamada (@roykamada) April 25, 2016

However, as our activity commenced, and while using Hypothesis to annotate this given webpage, I quickly found myself simultaneously reading and writing across multiple settings. My improvisational practices were both grounded – in text, in conversation – while also unhinged – thrown across networks and platforms. Unlike a flash mob where I might dance with others in a park before dispersing as if nothing occurred, my practices in this annotation flash mob were circuitous, weaving among the following platforms and practices:

- Utilizing Hypothesis to annotate in the margins of Sean’s article;

- Promoting and responding to tweets about the flash mob via Twitter;

- Reading notifications about annotations sent to my email;

- Accessing – via email – the Hypothesis stream and then responding to threaded exchanges (rather than by responding to annotations directly on the webpage); and

- Curating distributed resources – other media, articles, and related webpages – via hyperlink within layered annotation.

And all this cross-setting reading and writing left traces, bread crumbs as evidence of activity primarily in the form of Twitter and Hypothesis notifications sent via email. Here’s a screenshot of my email’s trash toward the end of the flash mob:

As much as I was reading a given text and (re)writing a growing and divergent set of conversations associated with that text, the flash mob required that I was also read and shape patterns of emergent interaction across networked settings. I was reading and writing back-and-forth across the multiple settings of a budding learning ecology. I was developing, sometimes awkwardly and through trial-and-error, a more unified approach to comprehending the unfolding text/s of interaction. What began as activity in the margin quickly spread – via Twitter, via email, via the Hypothesis stream – into cyclical and cross-context discussion. Seldom – in my experience as an educator and a learner – has a designed activity so quickly (within mere minutes!) morphed so as to demonstrate Freire’s classic concern for reading the word and reading the world.

This circumstance was even more complex and compelling because of the content that focused our flash mob’s collective expression. Consider this example from Robin DeRosa:

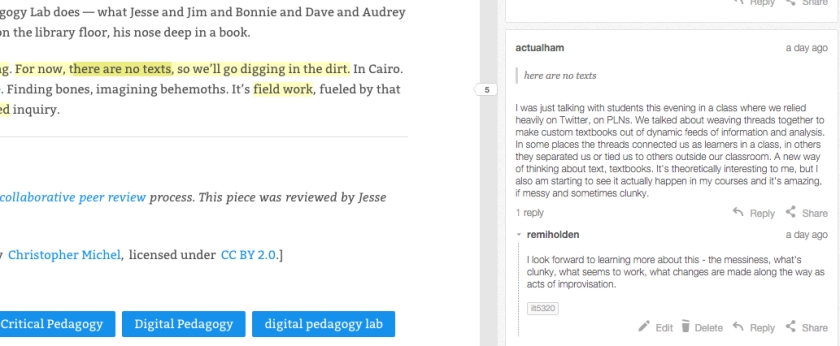

In response to Sean’s observation that “there are not texts” when designing a more human approach to digital teaching and learning, Robin recalled a recent experience with her students, noting: “We talked about weaving threads together to make custom textbooks out of dynamic feeds of information and analysis. In some places the threads connected us as learners in a class, in others they separated us or tied us to others outside our classroom.”

Robin’s comment about threads, connection, and separation resonates strongly with my experience reading and writing the flash mob as an in-the-moment event. Was I the only person who read and wrote this flash mob as threads connecting me with other people and ideas, while simultaneously loosing tangents of creative thought from the broader cloth of conversation? In what respect did others find themselves reading and writing across patterns of engagement because of specific points in an article? And am I missing other settings and practices that helped seed and propel participation in this flash mob? If so, please share.

Despite the fact that Hypothesis anchors annotation to specific text, I was not expecting that bursts of collective anchoring would result in such agile and trans-spatial reading and writing. As such, I’m left with additional questions that specifically concern the intentional inclusion of such an annotation flash mob in more formal learning arrangements.

- Should such cross-setting activity be expected from this approach to synchronous open web annotation?

- If so, how might designers and educators support learners in developing literacies to capably and meaningfully read and write during such threading, connecting, and separating activity?

- Is appropriate to assess such activity (and it may not be!)? And if so, how might educators chose to do so given a range of social reading and writing practices?

The following tweets provide a few glimpses into broader opportunities, challenges, and unresolved questions associated with annotation flash mobs as an experimental approach to social reading and writing in the open:

@remiholden @roykamada @slamteacher @hypothes_is @HybridPed Excited, but in a bit of a lurker mode 🙂

— Susannah Simmons (@thelearnersway) April 25, 2016

@remiholden @hypothes_is and my fifteen minutes are done! Great start on the flash mob. Looking forward to checking in later

— Lainie H (@unevoie) April 26, 2016

Really enjoying reading @slamteacher in community with @remiholden and company. Love this esp this from @roykamada:https://t.co/WUpIWYHGmF

— Dr. Dean (@dr_jdean) April 26, 2016

On the importance of playful learning, via the improvisational practice of playful annotation https://t.co/0sH7uiYWNq #digped #ILT5320

— Remi Holden (@remiholden) April 26, 2016

@onewheeljoe @vtelive last time I checked Joe, u were in charge of badges. both got credit on my bar tab, at which time we’ll discuss grades

— Remi Holden (@remiholden) April 26, 2016

Love[d] getting to play in the digital annotation flashmob. Thanks for inviting everyone to participate @remiholden & @slamteacher

— BritniBrownO’Donnell (@BMBOD) April 26, 2016

Reading Britni’s comment – “Love[d] getting to play in the digital annotation flashmob” – I’m reminded of the frequently referenced analogy of the digital mimicking sandbox play. When children play together in a sandbox they utilize a range of tools – shovels, buckets, toys of various shapes and sizes. While playing in this setting, children often act in response to their built yet flexible environment – all this sand, all these possibilities! They navigate among shifting social relations – first we’re builders, now we’re enemies, now it’s time for tag – all while pursuing emergent goals, from castle construction, to destructive battle, to collaborative artistic expression. Children’s activity is socially and materially situated, with interaction both intentional and improvisational.

This annotation flash mob created similar sandbox conditions, yet the playfulness of our reading and writing spanned settings. While our annotation was socially and materially situated in a particular place and time, so too was it mediated across connections and networks. Though fleeting, these new social relations – and the emergent goals of associated conversation – helped model a promising practice of inviting play for more open-ended, connected, and interest-driven learning.

As part of my general lack of enthusiasm for how the OER movement galvanizes itself around the idea of no-cost textbooks, I have started to become more interested in what happens to the “textbook” when it is opened by the Creative Commons license. That thinking is starting to make me wonder how far I take a reconceptualization of the textbook. How dynamic can they be? how unstable? how learner-created? How many levels can they have? How much contradiction and conversation can they contain? Anyway, I know this is a bit off the topic, but Hypothes.is seems like an interesting part of this exploration for me. Maybe a pathway to a much more exciting definition of “open textbook.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

This resonates with a question I’ll need to engage with two upcoming courses – one this summer, one next fall – that rely heavily upon central texts. In the past, I’ve been very traditional in my approach to textbooks – have students order, pace out the readings, yadda yadda. Given your thoughts – accompanied by this course’s various experiments in more open learning, and the subsequent feedback I’ve received – I’m now wondering, “What learning practices are afforded by open(ed) textbooks?” How learner-created? I like the idea of learners contributing to a growing archive, collectively curating the resources they feel are useful. How much contradiction and conversation can they contain? Including resources annotated with Hypothesis seems like a productive step in that direction. How unstable? I’m not really sure what this means… and I’d like to know more. I very much appreciate these thoughts, and I’ll be sure to keep you updated as my next set of courses develops.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think about instability this way: that most textbooks are (frustratingly) stable and unchanging. When they do change, it’s usually either overdue (history/politics have shifted in the world without updates to the book, for example) or underdue (early American lit textbook changes paginations and a few other things to require students to purchase new editions). But when the next book comes out, it’s a new book. We tend to think of stability as a positive word, but with textbooks, I think it’s mostly a drawback. I am curious about what happens if we start to see the value in educational instability, and think of our learning materials as more dynamic, as knowledge as never fixed. I know none of this is rocket science in theory, but the practice of valuing the stable artifact is so ingrained, it still seems radical to think about moving in this direction in our courses, in publishing models, etc…

LikeLike