A few days ago, Robin DeRosa – open pedagogy advocate and superstar Hypothesis annotator – shared the following via #digped on Twitter:

Have a good post abt the concerns of Ss working in public? Looking for PRO-open, with good ideas for managing challenges. Please RT! #digped

— Robin DeRosa (@actualham) February 26, 2016

I read Robin’s invitation as an opportunity for me to advance my own thinking – and continue my own writing – about INTE 5320 Games and Learning graduate students bloggers, annotators, and players who are working in the open this semester.

Some background: My approach to course design and pedagogy is influenced by an ecological approach to learning (read my related thoughts about designing a DS106 course last summer). I intend for a course, like Games and Learning, to create the conditions for learners to access new ideas and networks, to share information, and to generate knowledge across an ecology of multiple settings. Some of those settings are academic, while others are social; ideally, learning across those settings is connected. Learning, in the best of cases, spans a variety of everyday contexts, from classrooms to online blogs, from LMS platforms to social networks, from neighborhood encounters to interest-driven interactions. Accordingly, my approach to open course design and pedagogy extends public participation to connected and cross-setting agency.

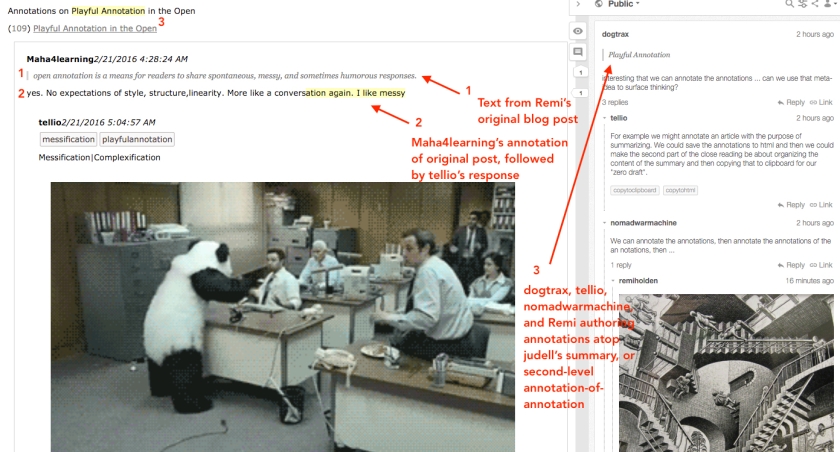

This semester, our learning in INTE 5320 is shared at various public scales – from individually authored blog posts (see our blogroll, at right) to collectively networked conversations via Twitter (follow #ILT5320). We have also begun experimenting with Hypothesis, a tool for open web annotation. I’ll address Robin’s request by sharing some challenges related to public annotation in the open. These challenges are not concerned with the technical affordances of Hypothesis as a tool; rather, they are associated with open annotation as a practice. Over the past few weeks, I’ve begun blogging about our planned annotation-as-discussion, as well as students-as-readers’ initial annotation practices and the playful qualities of their open annotation.

Here are three concerns about working with annotation in the open, and the contingent solutions that have defined the first few months of Games and Learning.

1. Identification and ownership: Some learners were initially concerned about publicly identifying with their open annotation, and subsequently owning the ensuing discussion.

There are 12 graduate learners enrolled in INTE 5320 this semester. How are they publicly identifying via their chosen Hypothesis handle? The course has split equally in thirds. Four have adopted a handle that combines a name initial with either their first or last name; with a little digging, a savvy reader could discern the individual associated with the given Hypothesis handle. Four have chosen a handle that combines their first with last name (as have I, remiholden). And four have chosen a handle combining either a personally meaningful or entirely random assortment of letters and numbers; in these instances, it is nearly impossible to identify who is authoring the associated annotations.

I did not provide recommendations about how annotators should create their Hypothesis handle. Chosen handles indicate a range of preference – from assured anonymity to full identification. It appears as if personal identification (and, in some cases, concern) may be related to comfort owning learning in the open: the greater an individual’s concern, the more likely she may annotate anonymously; less, or no, concern often leads to more public ownership of annotation.

My contingent solution: Honor learners’ decisions as they embrace a range of identities to annotate in the open. While I know each of my annotator’s Hypothesis handles (for course administrative purposes), I must respect their desire for public work to sometimes mean anonymous expression.

2. Assessing annotation: Learners have been concerned about my assessment of their open annotation.

How frequently should readers annotate a course text? By what standards am I assessing the quality of either a single annotation or a collection of annotations? And might learners be assessed favorably if they annotate with more than text (for example, if they link to related resources, or embedded images or GIFs)? I am grateful that my class has raised these critical, honest, and necessary questions.

And no, I have not mandated a quantitative frequency for annotation – whether of a given text, or throughout a two-week reading cycle. And no, I did not create an a priori rubric to assess either a single annotation, or a reader’s annotation practice (and any rubric would invariably be co-constructed, like last year’s “crowdsourced” rubric for the Games and Learning affinity space project). And no, I had little expectation about the emergent semiotic qualities of annotation. The messier the media(tion), the merrier.

My decision not to formally assess learners’ participation in open web annotation is informed by own experience reading – and writing inside – books. When in college and graduate school, notes I made in a book’s margin most frequently served as a means to synthesize information or to express an opinion. Perhaps I shared annotations with a peer when studying for a quiz. Certainly I referenced my notes when writing a paper. In this respect, annotation was both a generative and a formative practice. No professor ever asked me to photocopy my annotations and submit them for approval. No professor ever required that I count and report a summary of highlighted lines of text to measure my comprehension. When the practice of annotation moves into the open – and becomes social and networked – should a formative and self-directed practice become a means for summative assessment? I think not.

My contingent solution: I encourage learner annotation as a practice that engages curiosity, pursues interest, and promotes experimentation – all without fear that this social practice will be quantified into a measure of some irrelevant objective.

3. Facilitating annotation: Learners have expressed concern about how best to turn open annotation into substantive discussion.

INTE 5320 adopted open annotation as a replacement for LMS-based threaded forum discussions. Not only is a single reader annotating a given text, readers are collectively discussing ideas, engaging questions, and sharing resources through their networked annotation. I previously wrote about the rationale for annotation-as-discussion as a shift that moves:

From the privacy – and primacy – of LMS (specifically Canvas) discussion forums to the public “playground” afforded by Hypothesis;

From the formality of pre-determined questions (which can privilege the scope and purpose of reading) to open-ended and less formal (re)action and exchange; and

From an instructor’s authority to center and control textual discourse to a de-centering of power through a fracturing of attention, interest, and commitment.

Our shift towards discussion as public, more open-ended, and de-centered has not, however, replaced the utility of active facilitation. I presumed readers would annotate text, but I was uncertain about the extent to which such annotation might remain isolated or disjointed. How, then, to design for more substantive annotation-as-discussion in service of shared critique or debate? Such dialogic annotation would likely require elements of planning, response, and encouraged collaboration. As our course began, I shared a set of generic annotation-as-discussion facilitator guidelines that – for better or worse – were largely modeled after LMS-based discussion expectations. Here they are, slightly edited:

- Annotate readings with thoughts, questions, highlights, confusions, and related resources.

- Present annotations that are both insightful and informal, and that invite others to contribute and respond.

- Ask follow-up questions during the back-and-forth of annotation.

- Reference complementary resources, recommended readings and media, and/or other experiences and insights that both deepen and broaden our collective engagement with course material.

- Respectfully challenge your peers’ lines of argumentation, helping us all to address blind spots in our logic or perspectives, to confront our biases, to check (if not also work against) our privileges, and to be a critic in the most encouraging sense.

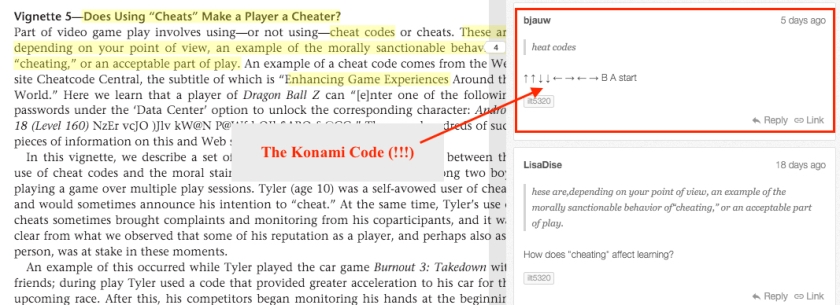

During the course’s first two-week cycle, I facilitated our annotation activities to model these fairly traditional discussion practices; my annotations asked questions, shared opinions, established connections amongst texts and ideas, and prompted responses to key ideas and general themes. The second cycle featured our first pair of learner-facilitators. Kirklunsford and LisaDise (yes, those are public Hypothsis handles) capably adopted many of the practices I modeled; they successfully sustained a discussion around three rather complex texts (complex in further introducing sociocultural learning theory and ethnographic descriptions of game play). Our third cycle of annotation-as-discussion concludes today. A second pair of learner-facilitators – SusannahSimmons and Hoffmaca – are continuing these practices. They have also embedded five scavenger hunt-style clues among the texts (here’s Clue #1). Peer response to this playful layer has been positive. This is another indicator that playfulness may “appropriate” open annotation (something I’ll write more about in a forthcoming post).

It may not help mitigate some learners’ concern that I have – and will continue to – avoid articulating so-called “best practices” for facilitating open annotation-as-discussion at the graduate level. And by the way, Hypothesis – to their credit – has done a great job developing education resources, including these annotation tips for students. However, these tips are just different than naming practices for discussion through annotation – and particularly for graduate learners. We’re less than two months into our shared endeavor – why cramp people’s creativity? I’m committed to describing how certain qualities of annotation emerge and are socially negotiated (such as playfulness). But I’m not very interested in making definitive claims about the relative effectiveness of this or that facilitation strategy. Our annotation-as-discussion is improvisational; this open experiment is not intended to build a decontextualized method.

My contingent solution: I will continue supporting learner experimentation with varied approaches to annotation-as-discussion. Open annotation can spark fascinating expressions of conversation, from playful flash mobs to civic annotatathons. In our open work, I anticipate continued ambiguity, confusion, and even frustration as we (re)shape this mashup of more formal academic discussion facilitation with informal and emergent social annotation.